The Cincinnati Subway

For many years people have been catching buses on Government Square; but where would you go to catch the Cincinnati Subway?... Believe it or not, a lot of people don't realize that Cincinnati has a subway. The main reason for this is because the subway has never been in operation.

The subway tunnel under the streets, has been silent and abandoned for over 50 years. It's entrances have been sealed with concrete and its tunnels are blocked by brick walls and steel fences.

Let's go back about a hundred years to find out why the Cincinnati Subway leads nowhere.

At first, there was the Miami and Erie Canal. This was part of the massive crisscross of waterways throughout Ohio and the Midwest. In 1850, the canal carried Cincinnatians and goods made in Cincinnati all over the country. But, in 1880, trains not boats, carried the majority of passengers and cargo. The canal became an unused, smelly backwater, except for the few children who still played in its filth. On September 27th, 1884, a Cincinnati newspaper, the "Graphic", told Cincinnati what it should do with its canal.

The newspaper printed a picture showing the stagnant old canal being replaced by a beautiful new street. And below the street's surface, was a subway for steam trains. The idea became the dream of the "Graphic" and it was the dream of many Cincinnatians.

At the turn of the century, Cincinnati was a leading trade center. It was one of the ten largest cities in the country and with its thriving businesses and industries, came a population that was growing beyond the downtown area and into its steep hills. This was a time when interurban electric railroads crisscrossed much of the country connecting cities and small towns. Nine major interurban rail lines converged on Cincinnati. The city wanted a swift way to bring passengers into the downtown area and public support was abundant.

In March of 1912, a three-man board of rapid transit commissioners was appointed by the county to find a way to make transit rapid in Cincinnati. A transit planner from Chicago was hired; and he came up with six workable plans for a rapid transit loop around the city. The plan which was selected had a $12,000,000 price tag which had to be slimmed down to a $6,000,000 version. The proposed loop around Cincinnati was to be 16 miles long. A short subway portion was to be built downtown in the old canal and would run in the canal to Brighton where it surfaced through the Mill Creek valley to Saint Bernard. It then hooked eastward through heavily industrial Norwood and southward through Oakley and Evanston to the river. It would run along the river on an elevated railway, back into the downtown area.

Cincinnati leased the right-of-way to a portion of the old Miami Erie Canal from the state of Ohio. $50,000 was raised for estimates and surveys. And what was just a dream in 1884, was soon to become Cincinnati's subway.

In 1916, with an overwhelming vote of almost six to one, the citizens of Cincinnati said yes to spending $6,000,000 to solve its transit problems; but for the start of construction, the answer was definitely no for the moment, because the United States had become involved in World War I.

Actual loop construction began after the war. There were a few minor delays because some Cincinnatians doubted that the $6,000,000 was going to complete the job. They felt that inflation from the war would cause costs to skyrocket, but the rapid transit board was not listening to any critics. On January 28, 1920, the first steamshovel. of ground was lifted from the canal at Walnut Street. The less expensive subway portion was to be constructed first because it was easy. You just laid the tubes in the drained canal. Well, easier said than done.

By early 1921, the inflation that some had only talked about, actually happened. Construction costs were way up and the money available would complete only eleven of the original sixteen miles. The entire eastern portion of the loop from Oakley into downtown would have to be eliminated, but this was only the start of the real problems.

Negotiations with the cities of Saint Bernard and Norwood delayed the project more than a year. Brighton residents delayed construction for over two months in 1922, because blasting for the subway was damaging their property. State examiners were always raising their eyebrows at the construction procedures and the financial records raised more than eyebrows in the state auditor's office.

The two mile subway tunnels were finished early in 1923. The aboveground sections of the loop were near completion by early 1927, but there was no money to equip any of it. Tracks had not been laid, several crucial links to the system were missing and the dollar balance in the books was near zero. The Cincinnati Subway, for the moment, was going absolutely nowhere.

Well, it wasn't all that bad; in October of 1928, Central Parkway opened on top of the subway using some of the right-of-ways purchased for the rapid transit loop.

Let's trace the rapid transit loop of the Cincinnati Subway system. The original plans or the transit loop began at 4th and Walnut Street near Fountain Square. Now, the old subway system was going to run north along Walnut Street to the canal, and then when it hit the canal, it was going to follow under Central Parkway up through the Mohawk and Brighton areas to Ludlow Avenue. The subway was constructed only to a point just north of the Western Hills Viaduct, with a short tunnel under Hopple Street that was never completed. The line would have then run above ground in the canal along a section which is now Interstate 75, to Saint Bernard. The loop would then tunnel under the business section of Saint Bernard and eastward in the open on private right-of-ways to a short tunnel under Montgomery Road in Norwood. It then would have run along a high retaining wall to another subway tunnel under Harris Avenue. Then it goes above ground again through the Norwood Waterworks Park, southward along Beech Street by the United States Playing Card Company to Duck Creek Road. The rest of the loop was never constructed but it would have run along a stretch of Interstate 71 to Madison Road. A tunnel would run under the Owl's Nest Park, through the hills to Columbia Parkway and along the Parkway on an elevated railway into the downtown area back to Fountain Square.

Only eleven miles of the sixteen miles proposed for the loop were completed and that's because most of the right-of-ways just weren't available. and funds ran out in 1927. The Cincinnati Subway was going nowhere financially, but the light at the end of the subway tunnel was not about to fade out.

A little more than two miles of unused subway tunnel lay beneath the streets of Cincinnati. The Queen City didn't know what to do with its $6,000,000 hole in the ground, and there were mammoth obstacles in its path. For one, the political atmosphere was changing. Murray Seasongood and a band of political reformers were not at all pleased that the county, not the city, controlled the rapid transit board.

By the time Mr. Seasongood was in City Council and Mayor of Cincinnati, he was convinced that it needed much more study and planning than it had received and he undertook to tell the public exactly that.

In 1926, Seasongood, as Mayor of Cincinnati, wrote a new City Charter and swept the Republican political machine out of City Hall. By 1928, he had done away with the rapid transit board. In its final report the board blamed inflation for all the problems and told Cincinnati that it would cost another $9, - $10,000,000 to save the subway. Nobody was interested in raising that kind of money, and in a few months it didn't matter because any plans for the subway ran smack into the great depression. Cincinnati needed jobs, not an expensive subway.

Even the crucial interurban rail lines that ran through the town were going bankrupt and the population of Cincinnati was spreading far beyond the area that could be serviced by the rapid transit loop. There was another new device for getting people around town - the motor car. Nothing serious was proposed for the subway system until 1936, when the Cincinnati Engineers Club suggested connecting the city's trolley system with the suburbs, through the subway tubes. But there was one big problem, the street-cars were too long to make the curves in the subway tunnels.

City Manager C. 0. Sherrill, in 1939, thought that if the trolley cars wouldn't fit, automobiles would. So he proposed that the city extend the subway under the crowded downtown streets to a large riverfront parking lot. The cars would have fit, but the cost to complete such a project wouldn't.

Shortly after World War II, a local business interest wanted to lease a portion of the subway from Plum Street to Ludlow Avenue, to bring railroad cars to businesses along the route. The station at Liberty Street (under the Burger Brewing Company) would be the main loading point. The City even approved a five year lease for the project before it was discovered that freight cars wouldn't fit through the subway tunnels.

After a comprehensive study in 1948, the City recommended that Cincinnati forget the whole thing.

The 50's, however, brought new threats to America - Soviet Russia and the Atom Bomb. So, someone came up with an idea that the subway tunnels would make a perfect underground fallout shelter. In the early 60's the federal government saw fit to renovate a particular station and install various items of equipment - toilet facilities, water facilities, heating facilities, etc. -so that it could be utilized by federal personnel in the event the need was necessary, and also, for both the county government and city government in the event of a disaster situation involving fallout. Government officials would assemble in the shelter facility and direct activities.

The city felt it got its money's worth when it came time to build Interstate 75 and the Norwood Lateral. Both highways are constructed on right-of-ways purchased for the rapid transit loops.

There were many ideas in recent years for something to do with the Cincinnati Subway. In 1969, the Diocese of southern Ohio wanted to hold a candlelight Communion service for 500 people, in what they called the 'Catacombs of Cincinnati'. The church officials couldn't get insurance. Meier's Winery wanted to convert a portion of the subway into an underground winery. Locally 'produced wines would be stored in the subway tunnel and tourists could visit, just like the winery in Silverton. The idea was turned down by the city. In 1974, a local group wanted to lease a small section of the subway tunnels to create an underground Atlanta; it would include retail shops and a nightclub.

In 1977, the Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Massive Transit Committee proposed light rail massive transit system for Cincinnati, something like the one in Chicago. The line would connect the western side of town and the suburbs with the downtown area. The benefits would be less traffic congestion, clearer air, and it would save precious fuel.

Council member Tom Brush explains where the proposed line would run:

"We could do one of two things. We could bridge the Mill Creek and bring the line into the Union Terminal area where people could get off and transfer to buses, or we could bring it down to the riverfront; there's still some lines that would run down there. The other alternative, which is an exciting one, (we hope), is to link it in with the existing subway and bring it down across Central Parkway, down Main Street by the Post Office and bring it out to grade as it comes to the surface, down near the riverfront where again, people could get off, walk to work or transfer to bus lines."

The $6,000,000 bond issue voted for in 1916, was finally paid off in 1966. And with taxes and interest the final cost to the city was $13,019,982.45.

The Rapid Transit System

At one time many years ago, it was known that the Miami and Erie Canal would outlive its usefulness as a waterway for transportation. Various schemes were proposed for its utilization. The scheme that was found to be most favorable was for its use as a right-of-way for boulevard or parkway purposes. Later it was suggested that a subway might be built under the surface for the use of steam trains.

The purpose of the Rapid Transit System was to provide a method of transportation for the people from the outskirts of the City into the city, without running over local street railway lines.

The first step towards utilization of the canal was in 1911, when City Council passed a resolution asking the State to lease certain portions of the Canal to the City. In May of 1911, the Legislation was passed leasing the Canal to the City from Broadway to three hundred feet north of Mitchell Avenue. The City was to pay a 4% yearly rental based on its evaluation. In September of 1911, Council passed the resolution to use the right-of-way.

The next step taken by Council was in March, 1912, when it authorized Mayor Henry T. Hunt to appoint a Commission to suggest ways and means for securing high speed electric railway service. The Commission consisted of William Cooper Proctor, W. A. Julian, and Dean Herman Schneider. Because Council did not provide funds for this investigation, the Commission asked the Commercial Association, the Business Men's Club and the Chamber of Commerce, to raise money, which they did, $10,320.00. The Commission then hired Mr. Bion J. Arnold, of Chicago, as an engineer to make the investigation. In December, 1912, the Mayor received the Commission's report. Mr. Arnold offered six plans in his report. In his most favorable report, he stated that Cincinnati would be considered too small to justify the large expense necessary for an elevated road or subway, it was also true that on account of the unusual topography and the restricted downtown district, it might be considered as an exception.

Following passage of the bill authorizing the lease of the Canal to the City, a valuation on the Canal Property was set at $800,000. The lease was signed on August 29, 1912, by Governor Harmon for the State and by Mayor Hunt for the City, and in September, 1912, Council appropriated $32,000-00 for the first year's lease.

In May, 1913, the Legislature passed a Bill giving the City the right to extend the original lease of the Canal from a point 300 feet north of Mitchell Avenue to a point 1,000 feet north of the B & 0 Railway in St. Bernard. This lease was not entered into until March 28, 1922. The value fixed on this additional Canal property was $75,200.00, which meant $3,008.00 in additional rental fees per year. In September, 1912, Council provided $50,000.00 for surveys, preliminary plans and estimates of a rapid transit system. In June, 1913, Professor George F. Swain was hired to do this work.

In January, 1914, Frank Krug, as City Engineer, took charge of the work, and three more members were added to the Commission. In April, 1914, Mr. Ward Baldwin was engaged to make estimates for the electrical equipment. In January, 1915, Mr. Krug submitted a report of the work done during the preceding two years. This report proposed four different schemes. The report was accompanied by detailed plans and estimates, and the one preferred by the Commission was estimated to cost about $9,138,000.00 for construction and $2,456,000.00 for equipment and power. This scheme provided rapid transit around Cincinnati and its urban areas.

The entire route would have been about sixteen and one-half miles long.

The cost for this scheme was entirely too high for the City's budget and eight modifications were worked out and Modification "H" to cost about $6,000,000.00, was selected as the most satisfactory. This modification included a surface line in many parts of the transit system.

Now that a scheme had been selected for the Rapid transit, how was it going to be paid for? Bonds, limited to one-half mill for Interurban and Rapid Transit purposes. The Commission requested Council to authorize a bond issue of $6,000,000.00 so that work on the Transit System might commence. On March 14, 1916, Council approved such a request and in a referendum election held April 25, 1916, passed overwhelmingly, being 39,726 for the issue and 6,652 against.

On April 17, 1917, and carrying a vote of 30,165 to 14,286, an ordinance was passed by the people and the City was to build the Rapid Transit System with the $6,000,000.00 that the bond issue authorized. It also set the riding fare at five cents within city limits with universal transfers between all cars of the combined system. The ordinance was declared illegal by the Supreme Court of Ohio on March 5, 1918, on the grounds that in certain provisions in the ordinance, the City was lending its credit to a private corporation.

After the Supreme Court held the lease ordinance to be invalid, and no capital issues of bonds were permitted during the War, construction could not proceed. It was decided on May 18, 1918, to issue $80,000.00 of the $6,000,000.00 bond issue to proceed with contract drawings. However, due to the total exhaustion of the existing funds, in July 1918, engineering work was stopped for the remainder of the year. As soon as the $80,000.00 became available early in 1919, engineering forces reorganized and work proceeded on the contract drawings. On July 18, 1919, plans were submitted for Section #1, and the contract was awarded on November 17, 1919 in the amount of $500,000.00. Section #2 was awarded in the amount of $500,000.00 also, in November 1919. Section #3 was awarded on June 17, 1920, for $550,000.00. Section #4 amounted to $500,000.00 in April 1921, and in December, 1921, Section #5 was awarded for $150,000.00. Section #6 was awarded on April 14, 1922, at the cost of $325,000.00.

It was very evident at the close of the War that the entire "Loop" could not be built for the $6,000,000.00 that was voted for in April, 1916. In fact, construction cost had doubled during the War and without much prospect of any material reductions, it would have cost possibly $12-13,000,000.00 to build the entire loop even with the modifications adopted by running the line on the surface through St. Bernard, Bond Hill and Norwood.

It was therefore determined, as the western part of the system and the part from St. Bernard to Oakley would be the most productive of revenues, not to attempt the construction of the eastern part. It was estimated that for the $6,000,000.00, the line could be built from the Canal and Walnut Street, along the Canal through St. Bernard, Bond Hill and Norwood to Oakley, excluding the laying of the rails. Instead of running on the surface and in the streets it was planned to place the line from Spring Grove, on the Canal to Oakley entirely on private right-of-way on surface and in a subway without any grade crossings. The line on the surface and in the streets as originally planned was but a temporary arrangement at the best and was so intended while the present plan would provide a real rapid transit line from Oakley to the City on which high speed trains could be ran without any interference.

On June 6, 1924, bids were received for Sections 7, 8 and 9. This contract amounted to $1,100,000.00 and covered the next five and one-half miles of transit.

In October of 1924, the first six sections of the system were completed. This completed about six of the sixteen and one-half miles with the exception of the laying of rails, furnishing the stations, etc..

During 1924, the City of Norwood passed an ordinance granting the Rapid Transit permission to pass through Norwood and occupy certain streets beneath the surface. Negotiations were also started between the City and St. Bernard for similar permission to pass through that City which was not completed until June, 1925. This caused considerable delay in construction and when added to the unsuitable weather conditions during the winter, the completion of Sections 7, 8 and 9 was going to be delayed several months. This delay and a few other unexpected expenses caused financial worry. It would be necessary to omit the work from a point north of the B & 0 Railroad at Duck Creek Road to Madison Road in Oakley and probably some other parts at other locations. The entire right-of-way, however, had been secured and paid for. In order to complete the line to Oakley, lay rails on the entire part constructed, build five (5) additional stations and finish the others, about $1,300,000.00 of additional money was going to be needed.

Early in 1925, the Legislature passed an act permitting the Rapid Transit Commission to sell any surplus property not needed for rapid transit purposes, and credit the proceeds to the Rapid Transit Fund. With estimates on the surplus property coming in, the end of the Rapid Transit System was nearing, because there was not going to be enough money from surplus property to do what work was needed. Thus the end of construction on the Rapid Transit System, but all was not lost. In October of 1928, Central Parkway was opened on top of the old subway tubes.

Rapid Transit Construction Dates

| Section # | Origin | End Point | Cost | Contractor | Start Date | Completion Date |

| 1 | Walnut St. | Charles St | $500,000 | D.P Foley | 11/17/19 | Dec. 1921 |

| 2 | CHARLES ST | OLIVER ST | $500,000 | HICKEY BROS. | FEB. 12,1920 | NOV. 1921 |

| 3 | OLIVER ST. | 350' N. OF MOWAWK ST. | $550,000 | HICKEY BROS | SEPT. 1920 | FEB. 1923 |

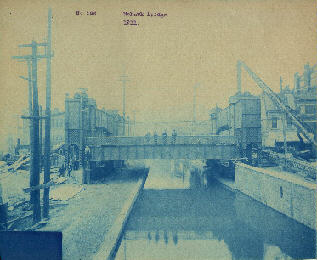

| 4 | 350' N. OF MOHAWK ST | BRIGHTON | $500,000 | F. R. JONES | JUNE 2, 1921 | JAN. 1923 |

| 5 | BRIGHTON | HOPPLE ST | $150,000 | HICKEY BROS | DEC. 1921 | FEB. 1924 |

| 6 | HOPPLE ST | MITCHELL AVE. | $325,000 | HICKEY BROS. | JUNE 1922 | OCT.1924 |

| 7,8,9 | MITCHELL AVE. | OAKLEY | $1,100,000 | HICKEY BROS. | JULY 1924 * |

*Proposed completion date was early 1925 (about 28%was completed by the end of the Sections 1,2,3 and 4 were of subway construction. Section 4 was the last section year 1924) of subway work in the Canal except for isolated subways under some streets.

The contract for Sections 7,8 and 9 was approximately 5 1/2 miles long.