Wildlife during the Total Solar Eclipse

- Mar 15, 2024

By Abby Ditomassi, Wildlife Education Coordinator, Division of Wildlife

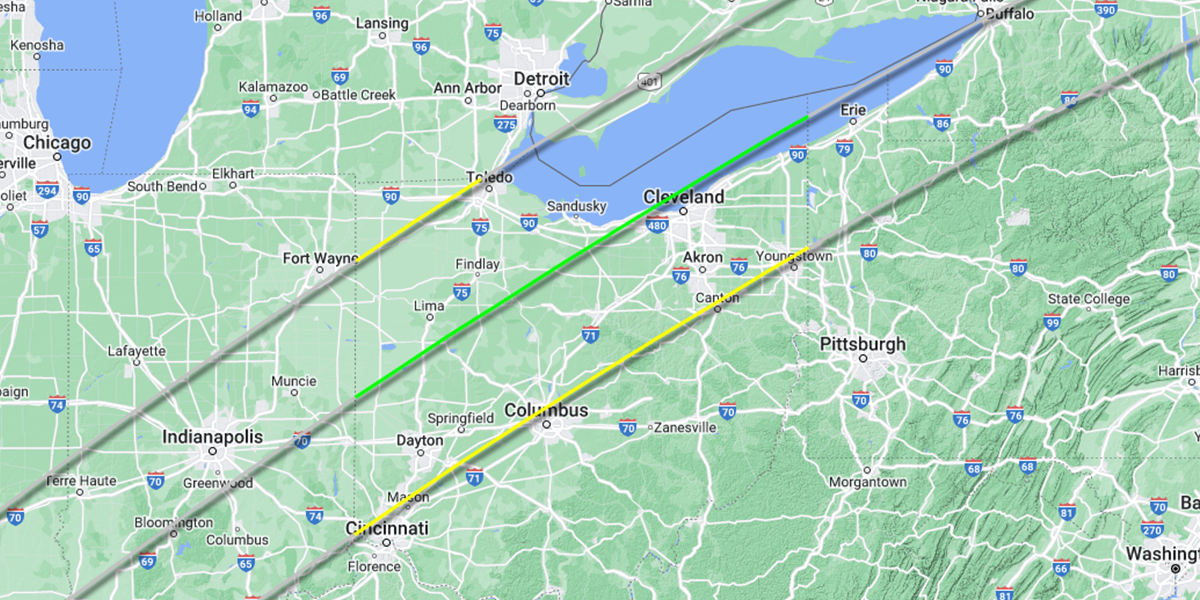

On April 8, 2024, a total solar eclipse will sweep over Ohio for the first time since 1806. There has been a lot of hype over this once-in-a-lifetime event since the next total solar eclipse in Ohio will be in 2099. While people all over the country may be looking up to the sky to experience the eclipse, I encourage you to look around and observe how wildlife reacts to this rare spectacle.

I experienced my first solar eclipse when I traveled to Tennessee with friends in August of 2017 to be in the path of totality. While I didn’t think to observe wildlife during the eclipse, the noticeable temperature drop as the moon blocked the sun’s light is hard to forget. During those few minutes of total darkness, swarms of mosquitoes came out to snack on me and my friends. This was quite unexpected! Thankfully, Ohio’s 2024 eclipse will occur in early April when mosquitoes are less active.

Since total solar eclipses are rare, most of what we know about wildlife behavior during the eclipses is anecdotal, like my mosquito observation. These anecdotal observations have, however, been supported by a few studies. According to a study conducted in Nebraska during the 2017 eclipse, which lasted for a total of three hours with 2.5 minutes of totality, light levels dropped by 67%, leading to a temperature drop of 6.7 degrees Celsius and a 12% increase in humidity. In the order Orthoptera, which includes crickets and katydids, it is known that the call frequencies lower when temperature drops and increase when temperatures rise. Field and tree crickets, normally nocturnal callers, increased their calls during totality, whereas cicadas and ground crickets, which call during the day, became quiet at totality. Birds also reported lower levels of call volume during totality for four different prairie and woodland sites, since most species call during daylight hours. The volume of bird calls then resumed to pre-eclipse levels after totality. Although bats and owls have been observed anecdotally during total solar eclipses, this study found no evidence of activity from these nocturnal animals. Other species have also been observed by researchers in other countries, such as honeybees returning to their hive during totality and orb-weaving spiders taking down their webs during totality, only to rebuild after the sun returned.

A very limited amount of data is available on fish, reptiles, and frogs during the eclipse. This is not surprising given the difficulty of tracing around the world to research wildlife during these rare total eclipses. Perhaps we should assist scientists by making sound scientific observations for them since millions of people will gather in the path of totality. Even if you don't take your eyes off the eclipse, listen for animals that are (or aren't) singing, such as songbirds, insects, frogs, and owls. You can use the Merlin Bird app or iNaturalist to record audio clips before, during, and after totality to make the data official. A project has been created on iNaturalist to collect observations on eclipse day. If you are interested in contributing to citizen science data through photos or audio, you can join the Ohio Wildlife Observations: Solar Eclipse 2024 project here. I hope to observe frogs and hypothesize that spring peepers will increase call rates as totality approaches and decrease rates to pre-eclipse levels after totality passes since they are usually nocturnal singers. What type of animal will you observe during the 2024 solar eclipse?

Check out more from Environmental Education Council of Ohio